ALEX

BELLAN

![[1.1] Home](exibition_fama_gallery_files/shapeimage_3.png)

![[1.2] Work](exibition_fama_gallery_files/shapeimage_4.png)

“DETRITI”

2013

Fama Gallery , Verona

text: Elena Forin

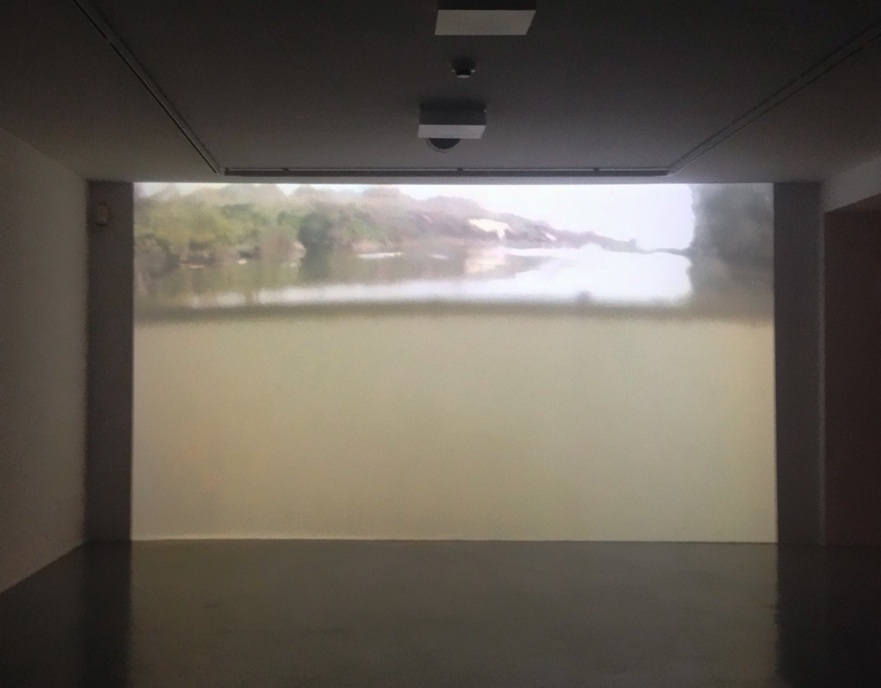

Detriti, un progetto che nasce da alcune delle sue riflessioni sull’identità di uno specifico concetto di “spazio”. Nel corso dell’ultimo anno, Bellan si è infatti concentrato su alcune e particolari dinamiche riscontrate nel proprio territorio d’appartenenza –l’area Euganea. Filo conduttore dell’intero progetto così come dei singoli lavori, è infatti un racconto che a partire da determinate frazioni di paesaggio, intende proporre un ragionamento più esteso, in cui le qualità di un ambiente modificato si dimostrano legate indissolubilmente alle dinamiche di invasione dello spazio naturale da parte dell’uomo. La prima opera a essere stata pensata è A seconda, il video proiettato a tutta parete nella grande sala del Basement. Realizzato grazie alla collaborazione con il Museo della Navigazione Fluviale di Battaglia Terme (PD) e prodotto dalla galleria, il lavoro prevede il monitoraggio, da parte di una telecamera galleggiante, del dedalo di canali che, a partire da Battaglia, attraversa campi e paesi fino a raggiungere il mare1. Nel percorrere questi canali, la telecamera incontra vari ostacoli e continui impedimenti generati dai tanti detriti -naturali o abbandonati dall’uomo- che popolano questi corsi idrici. l video, la cui lunghissima durata mette volutamente a dura prova la capacità di attenzione dello spettatore, è stato girato seguendo le modalità tradizionali dell’andamento a seconda, per cui la navigazione è unicamente affidata al ritmo e ai tempi delle maree. Una telecamera coperta e impermeabilizzata da uno scafandro, ha quindi galleggiato lungo tutto il percorso che da Battaglia giunge al mare offrendo non solo un inedito riscontro visivo a questa rete di canali, ma creando anche una connessione e un richiamo diretto a quelle forme e a quelle pratiche che hanno creato la cifra paesaggistica, visiva, culturale ed economica di questi luoghi. A emergere dalle affannose riprese a pelo d’acqua, è il senso di uno sforzo costante e intenso: la navigazione è infatti continuamente messa alla prova dai molteplici impedimenti che la telecamera incontra, che le fanno spesso invertire il proprio senso, annaspare tra i detriti, e lottare per proseguire il proprio percorso. In quest’opera in cui l’artista restituisce un’immagine complessiva dell’ambiente estremamente articolata, trovano posto sia una fotografia metaforica del paesaggio e delle sue più intrinseche motivazioni, sia un affondo concreto ed estremamente reale sulla natura, sui ritmi, sugli sforzi e le contraddizioni che hanno segnato la crescita e lo sviluppo di quest’area. È bene precisare tuttavia, che scegliere questi luoghi per l’artista non significa tanto condurre un ragionamento focalizzato su delle aree specifiche, quanto accendere l’attenzione su frazioni di paesaggio normalmente ignorate. L’idea non è quella di stare all’interno di una geografia precisa, ma di dar voce a una volontà di comprensione più estesa, che tocca idealmente ogni territorio. Per questo Bellan decide di intervenire su un altro tipo di struttura, questa volta un edificio, un ex macello, di cui, con una metodologia differente per tecnica ma simile per presupposti, ci mostra la più segreta struttura interna. Scelto per le proprie qualità di spazio che tendenzialmente non viene assorbito dal tessuto urbano, il macello viene presentato allo spettatore quasi come fosse un organismo di cui vengono percorse vene e arterie. L’artista infatti, attraverso delle sonde, realizza delle indagini endoscopiche nelle tubature rivelando una struttura inaspettatamente paradossale a causa delle continue interruzioni delle condutture. La sonda avanza offrendo allo spettatore immagini sgranate di uno sguardo che si avvicina senza mai tuttavia raggiungere un obbiettivo: proprio come in A seconda, con Ventre #2 lo spettatore si trova di fronte a una narrazione spesso contraddittoria, sovente interrotta e modificata dalla presenza di elementi di disturbo, e in cui a prevalere è il senso generale di una asfissia diffusa. A essere analoga nei due lavori è anche la percezione del tempo, che in entrambi i casi sembra condurre a un ulteriore smarrimento, dato sia da immagini al limite della visibilità che sembrano muoversi verso lo spettatore per inghiottirlo, sia per l’estensione di un percorso che è quasi infinito e che genera l’illusione di un’epopea interminabile. Tramite queste esperienze, rafforzate anche dalle altre opere esposte nel Basement, Bellan intende cercare una “forma di assorbimento” per questi luoghi: “voglio come integrarli nello spazio, mostrando la loro identità. Scavare nelle vie fluviali e negli edifici significa per me cercare una via di uscita o un punto di contatto inafferrabile”. Basamento, l’installazione scultorea composta da una leggera base sostenuta da quattro esili gambe di ferro, si colloca proprio in quest’ottica: i detriti collocati sulla base e tenuti insieme da cinghie elastiche rappresentano infatti la volontà – simbolica- di ricostruire i frammenti di una cava. “La trachite2 impiegata nel lavoro non è squadrata: viene dalla cave dei Colli Euganei. Questo tipo di pietra è stata usata in aggregazione con cementi per sostenere i tetti delle case. In questa forma non ha la sembianza di un materiale puro, e mi interessa proprio per questo, perché raccoglie la memoria dei gesti, dell’attrito accumulato su di essa dalle braccia degli operai che l’hanno usata, delle urgenze e degli scopi diversi per cui è stata utilizzata. Mi interessa tutto il percorso della lava trachitica, che emergendo ha smosso la linea dell’orizzonte con la formazione dei Colli Euganei: la sua asportazione con l’infiltrazione del gesto umano, l’estrusione, il trasporto lungo la rotta… il sostenere, l’emergere, il franare, e, infine, la sua riconversione attraverso quest’opera che riassembla la pietra con un gesto teso e vulnerabile (dato dalla cinghia)”. La tensione tra spazio umano e naturale di quest’opera si ritrova anche nell’ultimo lavoro esposto, A s-ciafà: la foto del varo di una barca negli anni ’30. Il natante, calato in acqua di lato secondo una pratica definita per l’appunto “a-sciafà”, viene completamente nascosto dall’acqua mossa dall’impatto. “I lembi della carta fotografica – dice Bellan- sono piegati quasi come se la modalità di realizzazione dell’immagine avesse “assorbito” il metodo raffigurato nella stampa: anche in questo caso cerco un punto di contatto, che si manifesta come una invasione dello spazio naturale da parte dell’uomo”. L’immagine è racchiusa dentro una piccola cassetta sormontata da una pietra trachitica. Il riferimento questa volta è al “cimitero dei burci”: “....negli anni ‘70 i vecchi barcari per protesta contro lo sviluppo delle vie di trasporto su ruota che toglievano loro il lavoro, affondarono le loro imbarcazioni, che nel corso degli anni sono riaffiorate”. In un certo senso, dice Bellan, il lavoro parla anche di questo.

![[1.6] Contact](exibition_fama_gallery_files/shapeimage_6.png)

![[1.5] News](exibition_fama_gallery_files/shapeimage_7.png)

![[1.4] CV](exibition_fama_gallery_files/shapeimage_8.png)

![[1.7] Link](exibition_fama_gallery_files/shapeimage_9.png)

![[1.3] project](exibition_fama_gallery_files/shapeimage_10.png)

“basamento” 2013

ferro , trachite euganea , cinghie

“A seconda” 2013

Video

15:00:00

“ventre”, 2013

3 video

00:03:00

“s-ciafà”, 2013

trachite euganea , foto , cornice di legno

Detriti, a project based on some of his reflections about the identity of a specific concept of “space”. Last year, Bellan concentrated on a few of the particular dynamics he observed in his own region – the Euganean area. The underlying theme of the entire project, as well as of the individual works, is a narrative that starts from certain parts of the landscape and then presents a broader way of thinking in which the quality of a changed environment proves indissolubly linked to the dynamics of man invading natural space. The first work to be created is ‘A seconda’, a video projected on all the walls in the large room of the Basement. Made in collaboration with the Museum of River Navigation of Battaglia Terme (PD), and produced by the gallery, the work involves using a floating camera to monitor the maze of canals that cross the fields and towns from Battaglia until reaching the sea1.While moving through them, the video camera encounters various obstacles and continuous impediments caused by the debris found in these waters, both natural and left by man. The video, whose very long length deliberately strains the viewer’s attention span, was shot according to a traditional sailing method entrusted solely to the rhythm and timing of tides (andamento a seconda). The camera, which was covered and waterproofed by a diving suit, then floated along the route that goes from Battaglia to the sea, providing not only an unusual visual account of this network of canals, but also creating a connection and a direct reference to those forms and practices that created the distinctive scenic, visual, cultural and economic character of these places. What emerges from the laborious filming of the water is the sense of an ongoing, intense effort: the navigation is constantly challenged by the numerous obstacles the camera encounters, which often cause it to change direction, floating around in the midst of debris, and struggling to continue on its way. Within this work, in which the artist renders an extremely understandable image of the environment, we find metaphoric photography of the landscape and its most intrinsic explanations and a very real and concrete thrust on the nature, rhythms, efforts and contradictions that have marked the growth and development of this area. It is worth pointing out, however, that the artist did not select these places so as to focus on specific areas, but rather to turn attention to those parts of the landscape that are normally ignored.The idea is not to be within a specific geographic area, but to give voice to a desire for a broader understanding that ideally touches every region. Therefore, Bellan decides to intervene on another type of structure, this time a building, a former slaughterhouse. Using a different technique, but with similar assumptions, he shows us its most secret internal structure. Chosen for their qualities of space that by nature are not absorbed into the urban fabric of the city, the slaughterhouse is presented to the viewer almost as if it were an organism with veins and arteries coursing through it. Using probes, the artist performs endoscopic examinations of the tubing revealing an unexpectedly paradoxical structure because of the continuous interruptions of the pipelines. The probe moves forward offering the viewer grainy images of a view that comes close to but never reaches an objective. Just like A seconda, with ‘Ventre #2’ the viewer is faced with a frequently contradictory narrative, often interrupted and modified by the presence of disturbing elements, and in which the prevailing feeling is a general sense of widespread asphyxiation. What is also similar in the two works is the perception of time, which in both cases seems to lead to further confusion since the images at the limit of visibility seem to be moving toward the viewer to swallow him up, and because the length of the path is almost infinite and creates the illusion of an endless epic. Through these experiences, reinforced by the other works exhibited in the Basement, Bellan intends to seek a “form of absorption” for these places. “I want to demonstrate how to integrate them into space, revealing their identity. For me, showing the rivers and buildings means looking for a way out or an elusive point of contact.” ‘Basamento’, the sculptural installation composed of a light base supported by slim iron legs, fits precisely within this perspective.The debris placed on the base and held together by elastic straps is in fact the symbolic desire to reconstruct the fragments from a quarry.The trachyte2 used in the work is not chiselled, but comes from the quarries of the Euganean Hills.This type of stone was used in combination with cement to support the roofs of houses. In this form it does not look like a pure material, which is why it interests me. It embodies the memory of gestures, the friction amassed by the arms of the workers who used it, the need for it and the different reasons why it was used. I am interested in the entire path of the trachyte lava, whose emergence has moved the skyline with the formation of the Euganean Hills: its removal by humans, its extrusion, its transport along the way… the support, the emergence, the collapse and, finally, its reconversion through this work, which reassembles the stone with a taut and vulnerable action (given by the strap)”. The tension between human and natural space in this piece is also found in the next work on display. ‘A s-ciafà’: a photo of a boat being launched in the 1930s. Lowered into the water according to a practice called “a-sciafà”, the boat becomes completely hidden by the water stirred up by the impact. “The corners of the photographic paper” – says Bellan – “are bent almost as if the way of creating the image had “absorbed” the method represented in the printing. Here too, I’m looking for a point of contact that is manifested as an invasion of the natural space by man”.